Greetings all! Alas, I am underway with my new blog in which I will explore a variety of topics related to Biblical studies, paying particular attention to the New Testament and other early Christian literature. With this being my inaugural blog post, I can think of no better topic to kick things off than an introductory primer concerning the composition dates of the New Testament Gospels. I intend to walk through some of the methods and thought processes involved in arriving at the most plausible date ranges for the Gospels – making application with a few of my own observations. Although this article is intended to be a primer and not an exhaustive treatment, a number of the concepts and conclusions put forth in this article will set the tone for other topics that I will discuss in the future.

Greetings all! Alas, I am underway with my new blog in which I will explore a variety of topics related to Biblical studies, paying particular attention to the New Testament and other early Christian literature. With this being my inaugural blog post, I can think of no better topic to kick things off than an introductory primer concerning the composition dates of the New Testament Gospels. I intend to walk through some of the methods and thought processes involved in arriving at the most plausible date ranges for the Gospels – making application with a few of my own observations. Although this article is intended to be a primer and not an exhaustive treatment, a number of the concepts and conclusions put forth in this article will set the tone for other topics that I will discuss in the future.

Arriving at the most plausible date ranges for the documents comprising the New Testament is a prerequisite to forming a cohesive and expedient understanding of the formative dynamics in early Christianity. In other words, knowing when a text was written is relevant to understanding why it was written, what the text means, to whom it was written, by whom it was written, how the text relates to the attendant socio-religio circumstances, and whether the text shares an interdependent relationship to other writings.

Unfortunately, the Gospel writers did not personally time-stamp their manuscripts. And even if they had, none of the original manuscripts have survived. At best we have only scribal copies of copies that are several generations removed from the originals, the single oldest authenticated fragment (Papyrus 52) dating to the mid-2nd century. Still, more than 80% of New Testament manuscripts date to the 5th century or later.

But this invites the question: when were the New Testament gospels written? A view commonly held by some in the conservative camp echoes the Church tradition that the Gospels were written by the evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John (in that order) a relatively short time after the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth c. 33 CE. For instance, Christian apologist J. Warner Wallace, author of the book Cold Case Christianity, proposes that composition of the gospels began as early as the 40s CE.

However, the dominant view held in mainstream New Testament scholarship is actually quite different. The prevailing view among today’s mainstream Bible scholars and even the majority of mainline Christian theologians, is the view that:

- The Gospels were written between the dates c. 70 CE and c. 100 CE.

- The Gospels are actually anonymous writings. The gospel writers do not purport to identify themselves anywhere in the texts; the titles we are accustomed to seeing were likely added later by scribes, taking note also of the fact that traditional authorship attributions do not appear in the record until mid to late 2nd century CE.[1]

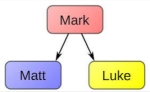

- Sequentially, the Gospel of Mark was written first around 70 CE and was followed by Matthew (80 CE), Luke (85-90 CE), and then John’s gospel (95-100 CE). The idea that Mark was the earliest gospel is called ‘Markan priority’, meaning that Mark was composed *prior* to the other New Testament gospels. Markan priority is accepted by a nearly universal consensus of Bible scholars.

For reasons that I will outline below, I am in general agreement with the mainstream consensus that the Gospels were most likely being composed between 70 to 100 CE. This date range means there are roughly 40 to 70 years between Jesus’ death and our earliest written narratives of his life and ministry. But again, can we actually know with any confidence the time-frame for when the gospels were written? In a word… yes.

How can we tell? Method & Application

First, we need to recognize that dating religious literature from antiquity is not an exact science. Yet, we do possess the tools and methods that will allow us to bring into focus a workable date range. What is needed in an examination of this nature is a willingness to ask proper historiographic questions without being constrained by tradition or preconceived assumptions, along with a willingness to seek out, examine, and synthesize the relevant data & evidence. And finally, what’s needed is a willingness to follow the weight of the evidence where it leads. Put simply – we should practice critical thinking. A salient principle that I learned while studying history in college and also while attending law school is that ‘evidence drives the conclusions, not the other way around.’ That principle will serve us well here.

There are two dates that define the range of any writing, namely the ‘upper limit’ and the ‘lower limit.’ The upper limit is the date after which a text could not have been written (i.e., the latest possible date of composition). The lower limit is the date before which a text could not have been written (i.e., the earliest possible date). To establish a practical date range scholars look to internal evidence (the content within the text itself), as well as external sources. For our purposes, external evidence is comprised of any probative evidence gathered from sources outside the gospel texts, such as the mention of the gospels or citations to them by other writers. External evidence could also include other relevant historical details germane to identifying the composition date.

By way of a modern-day illustration, if today I were to come across an undated letter that contains an ancillary reference to the tragic truck bombing of the Federal Building in Oklahoma City carried out by domestic terrorist Timothy McVeigh, then we can conclude solely from that information that the letter could not have been written earlier than April 19, 1995. That the letter itself directly references this event is the internal evidence, while historical knowledge of when the attack occurred and by whom is the external evidence. This combined data aids in establishing the ‘lower limit’ for the composition of this hypothetical letter, which in this case would be April 19, ’95. Of course, this does not mean that the letter was written on this date. But it does necessitate that the letter could not have been written prior to this date. So now that we have the conceptual basics down, let’s make application to our examination of the Gospels!

What’s war got to do with it?

As we all know, the Gospels tell us that Jesus was crucified in Judea at around 30-33 CE. This means that the Gospels were necessarily composed after c. 33 CE. But how long after? When it comes to evidence pertinent to establishing a lower date limit for the Gospels, the most glaring evidence would be that the Gospels make explicit reference to the Roman-Jewish War (66 – 73CE). Specifically, the Gospels refer to when Roman soldiers surrounded Jerusalem in 67 CE, and most notably the Gospels mention the complete destruction of the Jerusalem Temple, which happened in 70 CE (see e.g., Luke 21 and Mark 13). According to this scholarship, the Gospels were in all likelihood written after these events since they make direct mention of them. Nevertheless, those who espouse early composition dates for the Gospels ordinarily assert that the sacking of Jerusalem and destruction of the Temple as mentioned in the Gospels constitutes prophecy, and thus, the Gospels must have been written prior to these events – lest these prophecies attributed to Jesus be rendered as prophecies after-the-fact.

Setting aside for now the circularity of that view, to insist that the mention of the siege and Temple destruction within the Gospels be taken only as evidence of prophecy and not as evidence that the gospel writers had historical knowledge of these events amounts to a methodological double standard – especially when we are not equally charitable with secular/pagan writings attesting to would-be prophecies. If we’re going to appeal to customary academic considerations in our historiographic analysis of texts, then we have to be consistent in our methodology when we do so. We cannot make arbitrary exceptions.

For instance, the writings of ancient figures such as Pindar, Herodotus, Plutarch, Horace, and Virgil include purported prophecies from notable predecessors; and these prophecies often correspond to actual events. Yet, upon basic evaluation scholars universally recognize that these are in actuality prophecies post eventum. Given that the gospels must have been composed after 33 CE and there is no evidence proving that these texts were composed before 67 – 70 CE, then the potential window for the composition of the Gospels includes mid to late first century CE – which overlaps with the timeline of the Roman-Jewish War and Temple destruction. In other words, like the aforementioned Greco-Roman writings, the Gospels were composed appreciably contemporaneous to, or after, the events that are said to have been predicted. If we are going to be academically honest and methodologically consistent in our approach to examining ancient literature and Biblical history, then we are compelled to examine such matters in accordance with the same methods and pursuant to the same standards that are employed in our exploration of any other historical matter from antiquity. To do otherwise is to succumb to the fallacy of ‘special pleading.’

Having said that, I consider myself to be a fair and reasonable person. Thus, I am going to set aside altogether the whole matter of the Jerusalem Temple destruction. I will not factor in this event as evidence one way or the other in determining when the Gospels were written. Going forward, I will rely exclusively on other evidence to narrow down the most plausible date range for the Gospels. So let’s continue our examination to see what some of the other evidence yields.

Fathers know best?

At this point of the analysis we need to take a look at when the Gospels first show up on the historical radar. And as one might surmise, we would look to early Christian writings from the Apostolic fathers and Patristic fathers of the primitive church. Upon examining the record, we find that the four Gospels do not receive mention or attestation in the writings from any of the earliest Apostolic fathers ranging from 60 CE to at least 115 CE. This conspicuous silence has long been acknowledged by secular and Christian scholars going as far back as 17th century theologian Dr. Henry Dodwell who wrote:

“We have at this day certain most authentic ecclesiastical writers of the times, as Clement of Rome, Barnabas, Hermas, Ignatius… who wrote in the order wherein I have named them, and who wrote after all the writers of the New Testament. But in Hermas you will not find one passage or any mention of the New Testament [Gospels], nor in all the rest is any one of the Evangelists named.”

If the Gospels had already been written, circulated, and known in the Christian community as early as the 40s or 50s CE, then we are left to ponder how four of the earliest Christian sources from 60 to 115 CE (with many hundreds of pages of literature between them) could neglect attestation to any of the Gospels or display absolutely no awareness of the evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John. Any number of explanations could be posited to account for this silence; yet the most obvious and conspicuous answer is that these early Christian writers could not cite or mention texts that had not yet been written (or were in the process of being written and newly circulated).[2]

Justin Martyr

The first ostensible quotations of the Gospels come in the writings of Justin Martyr around 155 CE. Notably, though, when Justin cites verses that appear in our Gospels, he does not indicate that they were ever named Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John. In fact, he does not refer to this literature as “Gospels” at all. Justin never delineates or otherwise distinguishes these writings into individual texts or specifically identified authors. To the contrary, Justin refers to this literature as a generic corpus that he called the “memoirs of the Apostles.”[3] Regardless of the manner by which Justin referred to them, he seems to be familiar with some form of Gospel literature (even if the traditional authorship names were not attached). Accordingly, his writings in the 150s CE represent the first credible attestations to the New Testament gospels. From this data we can conclude that the Gospels must have been written sometime between 30 CE and 150 CE.

In view of the details above, one creates difficulties in maintaining dates of 40s to 60s CE for the composition of the New Testament Gospels, but failing to account for their attestation and reception in the Christian community until at least mid-2nd century CE. The ignorance of the Gospels by writers before Justin is better explained by them not being available or known in Christendom than by an assumption that earlier writers from 60 CE to well into the 2nd century (e.g., Barnabas, Clement, Hermas, Ignatius, or even Hegesippus – the first early Church historian) did not find them useful or authoritative. Let’s see if we can drill down even further…

Papias

The tradition that Mark and Matthew wrote Gospels is commonly traced back to the writings of 2nd century Church father Papias of Hierapolis (c. 110 – c. 150 CE).[4] While Papias refers to texts that he attributes to Matthew and Mark, there are several scholars who have aptly noted that we should not be so certain that Papias had in mind those texts appearing in the New Testament. There is indeed reason to suspect that Papias was not talking about our “Gospel of Matthew.” To start, Papias described the Matthew text as logia (“sayings”) written in Hebrew or Aramaic. However, our canonical Matthew is a Greek literary narrative that is textually dependent on Mark, which itself is an original Greek text. Papias also refers to Mark as a collection of logia (“sayings”) and as a non-organized compilation of ‘chreia‘ (short, pithy anecdote) without regard to proper sequence. Papias does not suggest at all that Mark or Matthew are parallel narrative accounts that follow a structured chronology and common plot. These represent a few of the reasons that some scholars question whether the Mark and Matthew that Papias described are the same Mark and Matthew that appear in the New Testament. If these are not the same texts, then there are two implications that follow: 1.) Papias cannot be cited as a witness to the New Testament Gospels; and 2) the authorship names traditionally associated with the New Testament gospels were being used for multiple unrelated texts. Notwithstanding all the above, for purposes of this article, I shall assume arguendo that Papias did have in mind the Matthew and Mark of the New Testament.

Papias does not discuss any specific content in these gospels; but regarding the provenance of Mark’s gospel he maintains that Mark was the translator for Peter and that Mark compiled a gospel from memory based on some of Peter’s teachings while he was alive. Papias explains:

“Mark, having become the interpreter of Peter, wrote down accurately, though not in order, whatever he remembered of the things said or done by Christ. For he had not heard the Lord or been one of his followers, but later, one of Peter’s. Peter adapted his teaching to the occasion, without making an organized arrangement of the Lord’s sayings, so that Mark committed no error while he thus wrote some things as he remembered them.” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 3.39)

Irenaeus

Next comes Church father Irenaeus of Lyon, France (c. 180 CE). Irenaeus, writing roughly 150 years after the time of Jesus, is finally the first Patristic source to mention all four Gospels by name. It is within Irenaeus’ major five-volume work ‘Against Heresies’ that he formally introduces the Gospels according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John as being the only acceptable Gospels for the church.[5] In discussing the Gospel of Mark, Irenaeus echoed the remarks of Papias, explaining that Mark’s gospel was written after the deaths of Peter and Paul. He writes:

“…Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome, and laying the foundations of the Church. After their demise, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, did also hand down to us in writing what had been preached by Peter.” (Against Heresies III.1)

In our undertaking to establish workable composition dates for the Gospels, the most crucial item to note from both Papias and Irenaeus is that the Gospel of Mark was written after the deaths of Peter and Paul. Why is this such a key piece of information? Well, according to Church records as detailed in the “Chronicle” of church historian Eusebius, the thirteenth or fourteenth year of Emperor Nero is given for the deaths of Peter and Paul. This means that Peter and Paul were killed in 67 or 68 CE![6] To connect the dots, the Gospel of Mark, our earliest gospel account was written at some time AFTER. So, what d’ya know… we are right back to ~ 70 CE for the earliest possible composition date.

Now it is worth noting that prudent historical analysis would require an examination into the credibility and reliability of Eusebius, Irenaeus, Papias, etc. – which exceeds the scope of this article. But it bears repeating that even if we defer to the claims and testimony of those considered to be the most ‘authoritative’ early church sources, we have established with confidence that (at a minimum) the earliest Gospels were being composed concurrent with or after the Jewish War.

Another poignant observation is that as soon as the Gospels received attestation with their authorship names they became increasingly cited, quoted, and explicitly integrated into the writings of the Patristic fathers. From 60 to 150 CE we note virtual silence from the early Church relating to the Gospels. Then once the Gospels are first attested in the mid-2nd century, there is suddenly constant discussion of them. Justin made numerous references to the “memoirs.” But in-depth discussion and exposition of the Gospels exploded in late 2nd century when the traditional authorship names had firmly attached beginning with the writings of Irenaeus (c. 180), then Clement of Alexandria (c. 200), then Tertullian (c. 207), Origen (c. 230) and so on. This is not a coincidental correlation.

Luke’s Tell-Tale Anachronism

Earlier I mentioned that the Gospel writers did not personally time-stamp their manuscripts. Well, that’s not exactly accurate. I should amend that statement to say that the Gospel writers did not intentionally time-stamp their manuscripts. However, it appears that at least one of the Gospel writers left an anachronistic clue in his narrative as to the timeframe for his composition.

Occasionally, narrative writers will give inadvertent clues revealing when they wrote their story owing to the presence of anachronisms in the story. An anachronism refers to an object, event, or even a word that is mistakenly placed into a time period where it does not exist. Put simply, anachronisms are historical inaccuracies that result in chronological impossibilities. An easy way to illustrate this concept is by highlighting examples from movies. In the movie Dead Poet’s Society, which is set to the year 1959, the lone bagpiper plays “The Fields of Athenry.” That song wasn’t written until the late 1970s when it first recorded in 1979 by Danny Doyle. Thus, the notion of someone playing that song on bagpipes in 1959 is a chronological impossibility – or anachronistic. Anachronisms of this sort are tell-tale indications as to the earliest the movie could have been written. So even if you had no clue as to when the movie Dead Poet’s Society was filmed, the fact that it features the song “The Fields of Athenry” is definitive evidence that the movie could not have been produced prior to 1979, regardless of the time setting that the screenwriter intended to depict on film (i.e., 1959).

So, what does all of this have to do with the Gospel of Luke? Let’s take a look to see if Luke gives us a similar clue as to when he wrote his gospel. The birth narrative of Jesus as featured in chapter two of Luke’s Gospel speaks of an empire-wide or universal census requiring all the inhabitants of Roman territory to return to the land of their ancestry for purposes of census registration.

“At that time the Roman emperor, Augustus, decreed that a census should be taken throughout the Roman Empire. This was the first census taken when Quirinius was governor of Syria. All inhabitants returned to their own ancestral towns to register for this census. And because Joseph was a descendant of King David, he had to go to Bethlehem in Judea, David’s ancient home. He traveled there from the village of Nazareth in Galilee.” (Luke2:1-5)

There are several items of concern with Luke’s statement, and they are too numerous to discuss at length in the present piece (I quickly address one issue footnoted here [7]). But the main observation as it relates to our topic of dating the Gospels is that Luke’s claim of an empire-wide or universal census is anachronistic. There was never a singular universal or empire-wide census instituted by Caesar Augustus. The censuses under Augustus were taken intermittently among the distinct Roman provinces at separate times/intervals as the regional political circumstances dictated – these censuses were not uniformly decreed or taken simultaneously throughout the empire at any time.[8] In fact, there is no record or apparent possibility of a universal Roman census ever in the empire until Vespasian and Titus conducted a universal census in 74 CE.[9] That Vespasian was the first to pursue a massive universal enrollment was one of the notable items of his reign. Apparently, the author of Luke’s gospel wrote his narrative considerably after this innovation and was unfortunately unaware that this practice was not historically typical nor was it practiced by Caesar Augustus. Luke erroneously and anachronistically retrojected geo-political features from his contemporary paradigm onto his nativity narrative. Whoops! So, the takeaway from Luke’s historical gaffe is that we can be assured that the Gospel of Luke was composed after 74 CE, and probably appreciably so.

Briefly revisiting the implications of Markan Priority

The scholarly consensus holds that Mark was the first Gospel to be written. Mark, Matthew, and Luke are known collectively as the ‘Synoptic’ gospels because they tell so many of the same stories, typically in the same sequence, using the same literary framework, and often in the same words at times with verbatim agreement (thus, they are Synoptic or “seen together”). Because the Synoptic gospels have so much in common, and in view of the striking literary and rhetorical similarities evincing a textual relationship among them – the vast majority of New Testament experts conclude that Matthew and Luke knew Mark’s gospel as a source and incorporated Mark as a template for their own Gospels as they endeavored to expand or improve upon (and occasionally make corrections to) Mark’s narrative. To put this into perspective, Matthew incorporates about 600 of Mark’s 649 verses into his Gospel, and Luke retains about 360 verses of Markan material. All told, 97% of Mark is reproduced in Matthew and/or Luke.[10] Meanwhile, John’s gospel is quite distinct from the Synoptics in style, sequence, and in the stories it tells. Yet, some scholars have made strong arguments that the author of John was certainly aware of the “Synoptic” gospels – even if he did not copy that template.

In my view the argument for Markan Priority is compelling and supported by the aggregate weight of the evidence, though all the details cannot be set forth here (perhaps in the future). But for purposes of this discussion, I shall assume Markan priority as the proper intertextual relationship between the Synoptic gospels.

Bringing to mind again the claims from Papias that Peter relayed to Mark a non-organized compilation of Jesus’ sayings and that Peter would also adapt his maxims to the occasion without having conveyed them in any particular order, and that Mark’s gospel is not in proper sequence and that he wrote down “some things” as he remembered – it is then notable that both Matthew and Luke track Mark’s narrative so closely in sequence, literary structure, and vocabulary.

Let’s consider again the Gospel of Luke for a moment. The introduction to Luke’s gospel very plainly says that the author “investigated everything from the beginning, to write it out for you in consecutive order….” (Luke 1:3) The Greek word that’s translated as “consecutive order” is καθεξῆς (kathexés), which literally means ‘in proper sequence’ or ‘in order’, and is a synonym for ‘chronological.’ Except an interesting thing occurs with Luke’s gospel. Luke’s narrative actually follows Mark’s chronology of events very closely throughout – even more so than does Matthew. Yet Papias made a point to note that Mark’s account is not sequential/chronological as things happened, nor is it comprehensive. Mark simply wrote various sayings and pericopes, without respect to chronology, as he remembered them from Peter’s situational anecdotes. That both Matthew and Luke track so closely to Mark’s narrative and literary framework is itself probative evidence that ‘Luke’ and ‘Matthew’ likely knew Mark’s gospel and relied on Mark’s text as a source. This observation highlights just one of the arguments in support of Markan Priority.[11]

To conclude, the evidence establishes that Mark’s gospel was composed no earlier than ~70 CE, and the evidence buttressed by the strength of scholarly consensus maintains that Mark was the first gospel and was relied upon by Matthew and Luke. Then it necessarily follows through Markan Priority that Matthew and Luke were composed no earlier than the 70s and more likely in the 80s or 90s CE (or perhaps even later). [12] To conclude otherwise is to conclude against the weight of the evidence.

As for the date of John’s Gospel, other than a minority within the conservative camp who espouse a pre-70 CE date, virtually no one denies that John was likely composed around 95 – 105 CE. To this point Irenaeus asserts that John through his gospel wrote to “remove that error which by Cerinthus had been disseminated among men, and a long time previously by those termed Nicolaitans.” (Against Heresies iii.2). Cerinthus was prominent around 100 CE. So, if Irenaeus is asserting that John’s Gospel was written to correct Cerinthus, then that implies John’s Gospel was composed during or after the activity of Cerinthus. Finally, the famous P52 fragment of John’s Gospel dates to around the middle of the 2nd century. Though this fragment establishes a firm terminus ante quem of ca. 150 CE for the Gospel of John, factoring in time for composition, copying, and circulation of the text suggests that John was likely written a tad earlier.

~ Doston Jones

Follow me on Twitter @DostonJones

[1] This fact is conceded even among some notable conservative evangelical scholars such as Craig L. Blomberg, who stated: “It’s important to acknowledge that strictly speaking, the gospels are anonymous.” The Case for Christ (p. 26)

[2] Note on Ignatius: There are 15 letters bearing the name of Ignatius, yet only 7 of them are deemed by scholars to be mostly authentic. Some have posited that within these texts are one or two brief instances in which Ignatius could be referencing the Gospel of Matthew. For instance, Ignatius makes mention of the virgin nativity. But this begs the question of whether he is citing Matthew or if he is instead relying on non-Matthean creedal or liturgical material. A number of scholars think it is the latter, and I tend to agree. Here’s why… in the Ignatius letter to the Ephesians he writes: “Now the virginity of Mary was hidden from the Prince of this world, as was also her offspring, and the death of the Lord; three mysteries of renown, which were wrought in silence by God. How, then, was He manifested to the world? A star shone forth in heaven above all the other stars, the light of which was inexpressible, while its novelty struck men with astonishment. And all the rest of the stars, with the sun and moon, formed a chorus to this star, and its light was exceedingly great above them all. And there was agitation felt as to whence this new spectacle came, so unlike everything else above.” (Ig. Ltr to Eph. 19). Sure, Ignatius mentions the virgin Mary and even a star, but… what’s this stuff about her virginity being hidden from the devil, as well as her offspring and the death of the Lord? That’s nowhere in Matthew or any other Gospel text. Also, the notion that all the rest of the stars, and sun and moon formed a chorus to the star that pronounced the arrival of Jesus is also nowhere to be found in Matthew. Furthermore, Ignatius makes no mention of the Magi or that the star moved about the sky to settle over the place of Jesus’ birth. It seems quite apparent that Ignatius is not interacting with the text of Matthew at all. Notwithstanding his awareness of the virgin nativity, in telling this pericope Ignatius is relying on liturgical or creedal material that is foreign to the New Testament gospels. But even if we were to grant that Ignatius is relying on Matthew (which is a tenuous argument, and it implies that Matthew was the sole possessor of the virgin birth narrative), this brings the terminus ante quem for the Gospels to 115 CE. For a fuller discussion see article by R. Carrier entitled Ignatian Vexation.

[3] Related note: Justin evinced no knowledge of the book of Acts. In point of fact, Acts was never quoted, discussed, or mentioned until 180 CE by Irenaeus.

[4] The records of Papias are primarily preserved in the writings of Eusebius from the 4th century.

[5] Notably, it is Irenaeus who first relates the tradition that the author of Luke’s gospel was a companion to Apostle Paul.

[6] Additionally, Eusebius, in “The Ecclesiastical History,” purports to quote from Dionysius of Corinth in reiterating the prior claim from “Chronicle” that Peter and Paul died at or around the same time. Eusebius was courtier to Emperor Constantine and took on the role of historian for the early Church. Much of what we know about the pre-Nicene Patristic fathers and their writings is filtered through the pen of Eusebius. While it is certainly prudent to cross-examine the veracity and credibility of Eusebius’ claims, such goes beyond the scope of this blog post. Since Eusebius is regarded in Christendom to be the most authoritative early historian, I will (for the sake of argument) utilize the dates given by Eusebius as the dates for the deaths of Peter and Paul – 67/68 CE.

[7] As a preliminary matter, there was never such a migratory census in the entire history of the Roman Empire where all the inhabitants were required to travel to their land of ancestry for census registration. To the contrary, and as supported by historical records of various census decrees in Roman provinces, a Roman census would have required Joseph to register not at his ancestral home in Bethlehem but at his own domicile in the principal city of his residential “taxation district” – presumably somewhere in the region of Galilee (the location of Nazareth). Indeed, this was the whole point of census registration. As the political need required, a given Roman province was to gather an accounting of its residential population and resources for the purposes of taxation and governance. These census registrations of residents were executed at the governor level. And this is undoubtedly true under Caesar Augustus. An empire-wide migratory census as described by Luke would not only have been a logistical nightmare, it would have in effect undermined and completely defeated the governing purpose of tax-based census registrations.

[8] We have record of the Quirinius census (6 CE) that Luke references in 2:2, which was taken pursuant to the fact that Judea had recently been annexed into the Roman province of Syria after the death of Herod the Great. Since Judea had officially become new Roman territory, it was necessary for Augustus to order a census specifically of Judean inhabitants. See Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 17.355 and 18.1-2

[9] E. Meyer, Ursprung und Anfänge des Christentums, I.51. See also, T. Mommsen, Historia de Roma (citing to Phlegon and referencing to census lists); Pliny the Elder also remarks about the Vespasian enumeration of inhabitants in his volume Naturalis Historia (c. 77 CE)

[10] Mark Allen Powell, ‘Introducing the New Testament’ (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2009).

[11] Additionally, it highlights some apparent tension in the testimonies of Papias and Luke. Also note that as it pertain’s to dating Luke’s Gospel, if we consider that the 2nd century ‘heretic’ Marcion’s Gospel was some version of Luke, then we have to concede that some iteration of the Lukan text existed c. 140 or before.

[12] See generally, L. Michael White, From Jesus to Christianity (2004);

Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings, 2nd ed. (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000);

Mark Allen Powell, Introducing the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2009); and

Luke Timothy Johnson, The Writings of the New Testament: An Interpretation, 2nd ed. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1999)

Dotson,

Excellent analysis and clear and concise writing. I always say we lawyers are the best writers. Even if you had not mentioned that you were a lawyer, I would have known. Who else but a lawyer would have used “ancillary” and “probative” in a blog post. I hope it’s okay to mention that I noticed a few glitches you might want to correct. In discussing “anachronistic” you change the name of the movie from “Dead Poets Society” to “Field of Dreams.” In addition, there are two typos in this sentence:

The author of Luke’s gospel was apparently writing (written?) considerably after this innovation and was unfortunately unaware that this practice was not historically typical nor was it practiced of (by?) Caesar Augustus.

Again, great job! I am scheduled to teach an adult education course on “The Literature of the Gospel of Mark” this fall. I plan for the first session to be some basic early Christian history and I learned some things from your blog post that I can impart to my students.

Keep up the good work.

Best,

David Oliver Smith

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your kind and constructive feedback. A little ‘editorial fatigue’ there. Lol. It has been corrected.

Yeah, that ‘legalese’ is difficult to purge.

As for your course, I assume that you will be teaching from your book ‘Unlocking the Puzzle: The Keys to the Christology and Structure of the Original Gospel of Mark’. The book is on my current reading list!

LikeLike

Succinct, informative, and enjoyable. I am going to enjoy being a visitor here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your WHEN WERE THE GOSPELS WRITTEN AND HOW CAN WE KNOW? post raises a lot of fascinating lines of analysis. I like your legal mind. A few of your comments I think are open to challenges that you might want to think about. I’ve too many things to say in one comment, without it becoming unreasonably long, and I appreciate your post is not meant to be exhaustive, but maybe a few thoughts from me for now, if I may. For ease of reference, I will number them.

1. “At best we have only scribal copies of copies that are several generations removed from the originals”. ‘Several generations’ is a problematic claim. How many is several? Anyway, in principle, an autograph could stay in use for a long time, before it is worn out. Ditto for first copies of them. We have fragments, some substantial ones, from c. 200AD give or take 20 years. These early ones could just as easily be only a couple of copies distant from long-lasting autographs as they might be ‘several’ steps away. We just don’t know. Assuming a couple or ‘several’ is vulnerable either way. ‘Several’ is more likely if we are talking about much later copies.

2. The conservative claim that “that composition of the gospels began as early as the 40s CE” probably refers to something like a proto-Markan passion narrative. There is a good possibility about that particular narrative – you probably know the reasons why – but it is not provable.

3. “the titles we are accustomed to seeing were added later by scribes”. This is a big claim, and depends on too many assumptions to be reliable in my view. Jokinen makes some worthwhile points about the heap assumptions underlying that claim.

4. You are making a comparison of very limited value in comparing the very specific case of ex eventu remarking on the Timothy McVeigh bombing as against the very unspecific gospel remarks about the fall of the temple. Specific versus vague is an unfair test by which to judge the latter as ex eventu. My next point builds on this.

5. “the Gospels refer to when Roman soldiers surrounded Jerusalem in 67 CE, and most notably the Gospels mention the complete destruction of the Jerusalem Temple”. Of course Mark’s gospel particularly has no idea of the date. Mark is explicitly hoping that the disaster won’t be winter, oblivious to the fact that it played out from spring into the summer. Of four gospels, only one (Luke) is particular about Jerusalem being surrounded, but how else does one attack a walled city in the ancient world? In any case, the data can interpreted differently: this could be a disgruntled group waiting for the moment of destruction of Jerusalem’s most potent symbol, rather than a group looking back on it but with remarks that are still strangely vague.

6. Critiquing the predictions of the fall of Jerusalem only as ‘would-be prophecies’ is not really adequate evaluation, as there are other ways to categorise and evaluate them. Stripped of a religious perspective, realistically they can be categorised as a political prediction of something the group considered desirable, and one with a good chance of coming true. It had happened before too. Equating this with pagan ex eventu prophecies has some value, but as a lawyer I think you will also understand the value of judging each case on its own merits on a case by case basis. A reasonable political prediction of something the group desired seems to me to be adequate explanation.

I better stop there in case you want an opportunity to comment on the above, as I’ve already said rather a lot.

Best wishes

Colin

LikeLiked by 1 person

Colin, thanks for visiting my blog and thank you for the kind words! I appreciate your thoughtful comments. You raise several important items to consider:

1. When I speak of our earliest extant manuscript copies being several generations removed from the autographs, I am referring to each ‘successive’ copy as a generation. The view that our earliest and best manuscripts are scribal copies of copies is the view held by virtually every mainstream New Testament textual critic that I have surveyed on the matter including the renowned and departed Bruce Metzger. When considering the geographic distribution of these early mss coupled with their paleographic and papyrological features, there is really little to no question that our earliest mss are multiple generations removed from 1st century originals (especially the most complete and useful copies).

2. You stated: //The conservative claim “that composition of the gospels began as early as the 40s CE” probably refers to something like a proto-Markan passion narrative.//

Actually, I was not referring to a potential proto-Markan passion narrative. I am aware of that view. However, I was referring to canonical Mark (or something akin to canonical Mark, minus the “long ending” of 16:9-20). The view that Mark dates to as early as the 40s is espoused by James Crossley for instance.

3. The view that the gospels did not always bear the traditional titles is an evidentiary argument that I will set forth in my upcoming blog post. Stay tuned.

4. Okay, i will try to simplify it this way… either the gospels do make specific reference to the circumstances of the Jewish War and destruction of the Jerusalem temple, or they don’t. I think we both agree that the former is the case. It seems to me a bit disingenuous to recognize the aforementioned references as prophecy of specific events, but to ignore or discount the references as evidence of historical knowledge and/or awareness of events concomitant with the Jewish War and Temple destruction. Another key point is that we must have methodological continuity in our historiographic approach. When cannot deviate from academic considerations and treat the New Testament differently out of theological compulsion.

Also, even if Tim McVeigh’s name was omitted from the hypothetical letter but there was discernible reference therein to the Oklahoma City bombing incident, historians would still likely cite April 19, 1995 as a terminus post quem. As for the gospels, I maintain that there is sufficient specificity to evince historical awareness of the events at issue, most notably in Luke 21.

Even setting aside the issue of how we should treat the references in the gospels to the Temple destruction and siege of Jerusalem, there is still adequate external evidence to corroborate the view that the gospels were composed during or after the Jewish War – evidence that I outlined in my analysis.

Again, I appreciate you taking interest in my article and I thank you for your constructive input.

LikeLike

Hello, Doston, I very much appreciate your feedback.

Not meaning to start blog-tennis, just a few thoughts to clarify my position.

1. I think it’s common ground that we have copies of copies. I am only reserved about how many intervening steps there might be from case to case. There might be few or many. I guess you are using multiple as a synonym for several. Where we can observe textual variants branching out in developing families of variants, it’s clearer that we have more rather than fewer intervening steps – I think that says more than geography.

2. I’d forgotten about Crossley’s book on Mark. I think I looked at the reviews and decided it’s not for me. Relying on internal evidence can be very useful at one end of the spectrum and like reading tea leaves at the other. I’m not sure how far down the spectrum I’d find his book. Good point that there are others in the same camp.

3. I look forward to your blog about traditional gospel titles. I keep thinking of doing that in more depth myself, but that’s some way off.

4. I think we have common ground that there are some passages in the gospels that correlate with the Jewish war. I think I may be misunderstood here though. We’re both approaching this from a naturalistic perspective, not a theological one, so the default starting position is, yes, that passages of this kind in ancient literature are likely ex eventu unless there is evidence to the contrary. I’m not arguing for the supernatural, but rather that this can be taken naturalistically as a political prediction. I am also arguing that the default position does not dictate the conclusions we reach, and that in this case, in Mark especially, ultimately the best naturalistic reading is not the ex eventu one. I explain how I arrive at this conclusion in my blog, so perhaps it’s best for me to mention that, rather than clutter your page with thousands of my words. But one of my key points, in brief, is that we have unique pre-70AD evidence that a radical re-evaluation of the church-temple relationship was already well underway in the 50s, in Paul’s Corinthian correspondence. SOMETHING had already triggered that process of re-evaluation. The question is whether that unique evidence is better explained by something Jesus said (to which there is a seemingly guileless witness in Mark 14:57-58 for example) or by something else.

I appreciate you coming back to me. If I may, I’ll post the second half of my comments sometime soon.

LikeLike

RE-POST (unedited)

Hello, Doston,

If I may, here is the second half of my observations on your interesting post about dating the biblical gospels. Of course, it is for you to decide which, if any, of these points is of interest to you. I’m not in my reply making a case for alternative dates. (I aim to do so in a future post on my blog.) I’m just testing whether you arguments are watertight.

1. Apostolic fathers as a marker for dating

By way of looking for a date range from composition of the gospels, your post claims that “we find that the four Gospels do not receive mention or attestation in the writings from any of the earliest Apostolic fathers ranging from 60 CE to at least 115 CE”. But is that the whole story?

It depends what you mean by “mention or attestation”. Is this meant to exclude apparent quotes from and allusions to the Gospels? This after all is a feasible interpretation of the numerous brief passages, especially in Ignatius, the letter of Polycarp, etc., that correlate with the text of the Gospels. It’s not an unreasonable interpretation to take these as evidence of an acquaintance with Gospel texts, even if other interpretations are available.

In that light, it seems premature to speak of a supposed need “to account for this silence”. Quotes and allusions are inconsistent with silence. It can’t be said that something resembling an acquaintance with Gospel material isn’t there. It is there. A case for a terminus ante quem can be argued here – there is room for dispute.

Therefore, I think you are over-stating your case in concluding that the Gospels “had not yet been written (or were in the process of being written and newly circulated)” at the time of the apostolic writers up to 115 CE.

In light of the said material, it also seems a dubious claim where you assert that “The first ostensible quotations of the Gospels come in the writings of Justin Martyr”.

So I don’t think you have a watertight case here for giving the gospels a late terminus ante quem. Although, I’m not sure you will be too bothered about me contesting that anyway, since you seem to allow Mark a date close to 70AD.

2. Justin Martyr as a marker for dating

So, you allow that Justin at least, with his quotations in context of reference to ‘memoirs of the apostles’ provides a terminus ante quem. You seem to be allowing that despite your caveat about Justin not naming them. So there’s no need for me here to step into the separate question of whether gospels were anonymous or not in Justin’s time, since we now have a date range regardless. But since you raised it, I’ll just briefly register my opinion too, if I may.

I want to examine your claim that: “Justin never delineates or otherwise distinguishes these writings into individual texts or specific authors. To the contrary, Justin refers to this literature as a generic corpus that he called the “memoirs of the Apostles.” But is it right to say ‘never’? Justin does employ a taxonomy.

To be clear, first, Justin is here talking about memoirs which he also calls ‘Gospels’ (Justin’s Apology 106). Secondly, I’m not sure why you have omitted the fact that Justin seems to delineate one individual text as the memoirs of Peter. It is difficult to reconcile this with your assertion, as if leaving no room for doubt, that “Justin never delineates or otherwise distinguishes…”

Notably, Justin clearly wants to leave his opponent in the dialogue, Trypho, with the impression that he knows which apostles and followers these are. it may be worth thinking about why Justin would give his opponent that impression, by referring to Gospels drawn up by apostles and followers, if this were simply handing a gift to his opponent to call Justin’s bluff, by simply asking Justin to name the said apostles and followers. His bluff is not called. It implies that his knowledge of their authorship was familiar to others.

There’s more. Justin delineates the Gospels into two categories as “drawn up by His apostles and those who followed them”. Following on from the above, Justin’s sorting of Gospels into these categories could not have been possible unless they had names attached, some of apostles, some of followers (Dialogue with Trypho 103). Otherwise, there are no categories.

Similarly, how could Justin think of the first category as being from apostles without thinking of them with some names attached to validate the claim that they were drawn up by apostles? (The answer to that question obviously is not anonymity, since that just avoids his taxonomy.)

The above raft of data is more simply explained by some gospels going by names than by their being anonymous in Justin’s day. In my view therefore, the logic of Justin’s taxonomy eliminates ‘anonymity’ from the range of possible answers to the big question of why Justin is not more forthcoming about naming the Gospels. Other possible answers to this big question need to be subjected to critical evidence analysis too, but that’s for another post, I suppose.

I could make some side notes about the significance of the ways in which Justin’s data correlates with data in Papias and Irenaeus (which you will be familiar with) but that would make this reply unreasonably long (even more that it already is!).

3. Dating Mark

Here, I think you’re simply trying to show that traditional Christian arguments for pre-67AD dating for Mark don’t work very well. This isn’t quite the same thing as providing a high value scholarly case for a post-70AD dating, but either way, your argument doesn’t really get there.

You venture to show patristic evidence that Mark was written during or after the Jewish war, by virtue of it being written after the death of Peter (info from Irenaeus) and the said death being 67-68AD (info from Eusebius’ Chronicon): thus Mark’s Gospel being 67/68AD or later. Two problems with that, if I may. In his History of the Church, Eusebius relies on sources that say Mark was written BEFORE the death of Peter, not after. Your depending on Irenaeus thus becomes a moot point. You are left, if you so wish, depending on contradictions between church fathers in order to dispense with Eusebius. Unless there is a very good rationale for that, you could be vulnerable to a charge of cherry-picking. In any case, Irenaeus would hardly have been sufficient to bear the weight you put on him, because the word in Irenaeus is literally not the ‘death’ of Peter but the ‘departure’ of Peter. Of course, there is a fair chance that Irenaeus was using a euphemism for death, but you’re now reliant on ambiguity and contradiction to support selectively i) that you can dispense with Eusebius’ Histories on this point and ii) you can treat the ambiguous ‘departure’ as meaning ‘death’. As you know, the church fathers have to be handled with caution, whether you’re trying to prove traditional Christian arguments right or prove them wrong. One could try to construct a case from patristics to reach the conclusion you preferred, but it would be hard to avoid resembling a house of cards if the above is anything to go by.

4. Dating Luke

Switching from Mark to Luke, I want to examine your belief that, as you state it: “Luke’s claim of an empire-wide or universal census is anachronistic… Whoops! So, the takeaway from Luke’s historical gaffe is that we can be assured that the Gospel of Luke was composed after 74 CE, and probably appreciably so.” But is that doing the text justice?

The ESV translates Luke 2:1 accurately: “In those days a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be registered.”

You have probably anticipated me saying that this exegetical problem is thrown up by mistranslation. Your reading, “census… Roman Empire” is represented by the NIV and similar translations. So, the devil is in the detail here, and in the assumptions of translators. The specific Greek words matter here, which I’m sure appeals to your lawyer’s mind! Now, these words in Luke report a decree to REGISTER i.e. “apographesthai” (not literally “census”) ALL THE WORLD i.e. “pasan ten oikoumenen” (not literally “the Roman Empire”). That’s all we have to go on within the verse. Let’s break this down.

“REGISTER”: It is problematic here to follow the traditions of translators, and speculate on what “register” means. Clearly, we can’t absolutely assume without evidence that “register” means “census” (NIV), or “pay taxes” (KJV), or “register loyalty to Augustus” (see this worthwhile suggestion at http://str.typepad.com/weblog/2013/12/the-census-of-caesar-augustus-quirinius.html). I lean towards the last suggestion as the most consistent with the historical period, but I could be wrong.

If there are three such options, and we want to select the most clearly anachronistic of them, we need a good rationale for why we would do so (NIV translators ought to take note!).

Perhaps the wisest translation is to leave it ambiguous as “register”, admitting that we can’t put much weight on preferred meanings.

Secondly, “ALL THE WORLD”: Clearly we can’t absolutely assume it means “the whole geographic world”, and similarly we can’t absolutely assume the NIV’s interpretation that it means all of “the Roman Empire”, or that it just means “all Judea”. The question is, whose “oikoumenen” is it in Luke’s mind, given that the only illustrative example he gives merely takes a single couple to Bethlehem? The wisest translation, the course taken by the ESV again, is perhaps just “world”, admitting that we can’t specify whose “world” is intended. I lean towards ‘Empire-wide’ but I could be wrong.

CONCLUSION: There may be a watertight argument for dating Luke post-70AD, but this isn’t the one. The ESV proceeds with caution with good reason.

We really can’t be sure of your “Whoops!” That is, even if we were guided by an inclination to think of Luke as prone to mistakes, we have to choose which mistake – a pre- or post-70AD mistake based on Luke misapplying an awareness of Imperial oaths or paying taxes, or a post-74AD mistake of Luke misapplying an awareness of either of the above or an Empire-wide census. You are arguing the last option, for your late dating.

I lean towards this being about making an oath to Augustus, as the best fit with the period. If so, then Luke may be correct about it having happened, or – if you are inclined to a certain view of Luke – it may be a mistake made pre- or post-70AD, but there is no certain way of knowing which.

I don’t think we can date Luke’s gospel from this verse. In short, “the weight of the evidence” is open to discussion, not a closed case. I don’t know why you want to put so much weight on it.

5. Dating John

I’ve not much to say here, but I’d like to say a little based on early data. I admit to being surprised that your link supporting that “Cerinthus was prominent around 100 CE” was merely a link to Britannica! Allow me to take us in more detail to our earliest primary source, if I may.

Irenaeus tells us that Cerinthus was around in the lifetime of John the apostle when the latter famously ran out of a bath-house (a fit man to be running!): http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0103303.htm And that John wrote his Gospel partly in response to Cerinthus as you mention: http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0103311.htm (That’s in Against Heresies iii.11 by the way, not iii.2.) And also that John remained until the time of Trajan: http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0103222.htm

This means that IF we attach this Gospel to THIS John – are you really basing your dating on that assumption? – then it was written at the time of Trajan or an earlier Emperor. The traditional date of the Gospel on that basis could be right, but earlier dates fall within the scope of that data too, since we know little of the scope of John’s acquaintance with Cerinthus, nor Cerinthus’ age. If the Gospel is attached to a different ‘John the Elder’ instead, or another candidate, that widens the question of dating. I don’t think we are getting much nearer dating the gospels this way, but church tradition may be more or less right, which is what I think you are inclined to.

Final note

Weak links undo some of the thread of your argument, and I don’t think you have provided a watertight basis to date the gospels. But if you think I’m misreading anything, I am of course happy to take another look. If you have time to offer any feedback, that would be gratefully received. My apologies for the length of this reply. I hope you find some of it worthwhile for discussion. I’m finding this a really helpful exercise which is helping me to clarify some of my own thoughts.

LikeLike

Colin, my apologies for the delayed reply. I truly appreciate your constructive feedback, and I enjoy engaging readers. Your comments are quite lengthy and require a great deal of time and focus on my part in order to provide an adequate reply. I can’t address all the items you mentioned in this reply. I will have to break up my responses into separate posts. This post will focus on your comments related to Justin Martyr.

Re: your comments on Justin Martyr:

//I’m not sure why you have omitted the fact that Justin seems to delineate one individual text as the memoirs of Peter. //

I did not omit the fact that Justin seems to delineate one individual text as the memoirs of Peter because, in my view, Justin does no such thing. It seems that you are extrapolating beyond what Justin’s treatise actually says and you are offering a strained reading to Justin’s work.

As you have advanced in your comment above, Justin’s ‘Dialogue with Trypho’ (106.3) is sometimes put forth as an example of Justin citing to memoirs written by Peter (or even Justin citing to the Gospel of Mark). I think such an argument is tenuous at best. In Dialogue 106.3, Justin merely mentions a pericope *involving* Peter (and the sons of Zebedee for that matter), which he says is found written in the memoirs. To that I would say, ‘so what?’ We already know that Justin relates numerous things found in the Gospels, and that he cites “the memoirs” for this content. But he does not stipulate that it came directly from Peter or from Mark’s hand. Let’s take a look at the passage…

“You that fear the Lord, praise Him; all you, the seed of Jacob, glorify Him. Let all the seed of Israel fear Him.’ And when it is said that He changed the name of one of the apostles to Peter; and when it is written in the memoirs of Him that this so happened, as well as that He changed the names of other two brothers, the sons of Zebedee, to Boanerges, which means sons of thunder; this was an announcement of the fact that it was He by whom Jacob was called Israel…” (Dial. 106.3; Translated by Marcus Dods and George Reith. From Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 1; published on NewAdvent.org)

With regard to the phrase “and when it is written in the memoirs of Him that this so happened…,” I presume that you interpret “of Him” to mean Peter. This, I think, would amount to an errant rendering of the passage. In my reading of this passage, “of Him” is most assuredly a reference to Jesus. This view is supported by the weight of the scholarship that I have consulted on the matter, including multiple Christian sources. Four relevant observations to note:

1. To begin with, Justin on occasion refers to the Gospels under the collective appellation “in the memoirs of the apostles of Him” (εν τοις απομνημονευμασι των αποστολων αυτου). So as it pertains to Justin’s manner of citation to the memoirs, the singular genitive “of Him” clearly corresponds to the subject – Jesus. Put simply, Justin is describing the Gospels collectively as “memoirs of the apostles,” which are “of Jesus,” (i.e., about Jesus). This is not a title that is intended to single out the specific author of a text. Justin never does so with the memoirs. Even when Justin truncates the title to “memoirs of the apostles”, it is apparent that his convention is to refer to the authors as a single unitary class – ‘the apostles’ (not as individuals). It seems that for Justin, the collective reference to the apostles for provenance is itself sufficient for source identification.

2. As further indication that “of Him” in 106.3 is a reference to Jesus, in the very next line 106.4, Justin does in fact cite to “the memoirs of the apostles of Him”. This makes it all the more evident that Justin’s title reference to “the memoirs of Him” as found in the preceding line most likely flowed from the same train of thought and frame of reference. That the passage in 106.3 means “the memoirs of Jesus” is a view advocated by Christian NT scholar Paul Foster and numerous others. Under his interpretation, the Greek grammar best renders αυτου (“of him”) as serving an objective, rather than subjective, genitive, meaning that the memoirs are “about Jesus.”

3. Focusing our observation to lines 106.1 thru 106.4, Justin uses the male pronoun “him” no less than eleven times. And, if we ignore the single “of him” reference at issue here, it is unmistakably evident that EACH of the remaining ten uses of the pronoun “him” are in reference to Jesus personally. This is a very telling rhetorical pattern. In fact, Justin uses the male pronouns (“he” or “him” or “his”) a total of 31 times in Dialogue 106, and not once is it used in reference to anyone else other than Jesus (the same holds true throughout the directly preceding and subsequent chapters). Furthermore, in that same sentence and in the very next clause Justin writes, “as well that He [Jesus] changed the names of other two brothers, the sons of Zebedee”. Thus when Justin uses of the male pronoun “he” in this sentence as a reference to Jesus, which comes on the heels of “the memoirs of him” without any attempt to disambiguate the subject (as well as Justin’s continued and uninterrupted use of these same male pronouns in reference to Jesus), this further highlights a pattern of practice evincing that Justin’s use of pronouns “him” and “he” and “his” in this context is reserved solely for Jesus. To argue otherwise would be special pleading.

4. Lastly, and as stated above, the principal subject of Justin’s discussion and also the principal subject of the “memoirs” is Jesus. Though the story that Justin relates in 106.3 involves Peter (as well as the sons of Zebedee), the story itself is about Jesus and his deeds/actions as told in the memoirs about him. Accordingly, when Justin states “when it is written in the memoirs of Him that this so happened, as well as that He changed the names of other two brothers…” – he is talking about Jesus. To be sure, this is how the passage is understood in each translation that I have encountered, including the translation provided by Christian source ‘The New Advent’, which uses capital “H” in the pronouns He, Him, and His in these passages to signify Jesus’ divinity.

Even if Justin was referring to “the memoirs of Peter” (which I do not think he did), that still provides no evidence that the Gospel of Mark had been given its traditional title by Justin’s time. Justin does not refer to the Gospel of Mark by name in Dialogue 106.3, nor does he refer to any of the canonical Gospels by their traditional names. This provides evidence that their traditional titles had not been firmly attached to the texts by 150-160 CE. Otherwise, Justin would have called them by their traditional names, as Irenaeus (180 CE) and the Muratorian Canon (c. 170-200 CE) did a couple decades later, and as did the Patristic sources that followed into the third century CE.

Colin stated: // To be clear, Justin is here talking about memoirs which he also calls ‘Gospels’ (Justin’s Apology 106).//

You are correct that Justin in one instance says that the “memoirs” are called Gospels (First Apology 66). But this observation does not adversely impact my underlying thesis. I already stated that Justin was the first Patristic source to make repeated references to textual content that most ostensibly corresponds to the NT gospels (see also, related discussion in my most recent article). However, Justin’s preferred manner of referring to this literature was to call them “memoirs.” In his First Apology and in the Dialogue with Trypho, Justin used the term “memoirs” exclusively when citing to this literature – except for this one instance in First Apology, 66.

I think there is a reason Justin prefers “memoirs of the apostles” and avoids using the term “gospel” as an appellation for this literature. Yet, I wasn’t suggesting that the term was not otherwise associated with this genre prior to or concurrent with Justin. My primary concern was in identifying unambiguous external references to the New Testament gospel texts for purposes of drilling down on a terminus post quem. And Justin’s treatises serve that purpose.

But we know that the term ‘gospel’ was indeed associated with this genre of literature by this period. For instance, in my article discussing the anonymity of the Gospels, I noted that Marcion’s Gospel (which predated Justin’s writings) was called “the Gospel of the Lord.” I also mentioned that the Didache, another treatise in circulation at this time, referred to its source text as “the Gospel of the Lord” and as “the ordinances of the Gospel.” So yes, Christian literature prior to Justin attested to “Gospel” texts; but not in relation to any apostolic authors. Rather, the Gospel titles were in relation to its subject – Jesus. Even if Justin acknowledges (on just one occasion) that these texts were called gospels, there is no statement given by him or by any of the aforementioned sources that links this literature with authors Matthew, Mark, Luke, and/or John. In fact, I happen to think that Justin either acquired or adopted the moniker “memoirs of the apostles” as a means to give apostolic provenance to these “Gospels” that were theretofore anonymous.

Also, seems we can observe in Justin’s writings a subtle, yet informative, progression of the tradition. In Justin’s ‘First Apology’ he states: “For the apostles, in the memoirs COMPOSED BY THEM…have thus delivered unto us what was enjoined upon them.” (emphasis mine)

Justin here tells the reader that the memoirs were written by the apostles themselves; though he doesn’t tell us which apostles, as there were at least 12 among them (and conspicuously, Justin never once mentions Paul’s name nor does he ever cite to Paul’s epistles for theological/doctrinal instruction). Justin only says that the “memoirs” were “composed by them” (the apostles). He gives no indication whatsoever that any of these writings were composed by anyone else. Also, Justin never says that there were four memoirs/Gospels. He provides no enumeration at all. Likewise, in the First Apology, Justin says nothing about any memoirs being written by the followers of apostles. He simply states that the memoirs were WRITTEN BY THEM (i.e., apostles) and that they wrote in accordance to what they were permitted to experience with Jesus (e.g., the Eucharist, etc).

Now let us fast forward past the First Apology, and also past the Second Apology, and on to Justin’s Dialogue with Trypho where he writes for the first (and only) time that the memoirs were “drawn up by His apostles *and* those who followed them.” This is rather different from his prior representations in his Apology treatises. Perhaps this little extra tidbit reflects continued advancement/progression of the gospels’ literary tradition?

Colin stated: //Justin clearly wants to leave his opponent in the dialogue, Trypho, with the impression that he knows which apostles and followers these are. It may be worth thinking about why Justin would give his opponent that impression, by referring to Gospels drawn up by apostles and followers, if this were simply handing a gift to his opponent to call Justin’s bluff, by simply asking Justin to name the said apostles and followers. His bluff was not called//

Again, I think you are extrapolating far beyond what Justin says in the text. Justin does not say any of that. Like I mentioned above, Justin never even sets forth the number of memoirs/gospels let alone any specific names of authors – even though naming his sources is something that Justin was otherwise accustomed to doing. If Justin firmly knew the identities of the specific apostles and specific followers who were responsible for composing these texts (as opposed to a general reference class), then it stands to reason that he would simply mention them by name in that context. For instance, should we assume that Justin specifically had in mind “Luke, the companion to Paul” when in more than 225 total chapters of his works, Justin does not utter the names of Luke or Paul or Paul’s writings? (this opens up a whole line of interesting questions, actually) … It seems that for Justin, the collective reference to the apostles (and their close followers) for purposes of establishing literary provenance is itself sufficient for source identification. The reality is that Justin referred to these writings by the name he best knew, “the memoirs of the apostles of Him” (or some abridgement thereof). At any rate, Justin treats these texts anonymously, regardless of whatever ad hoc reason we come up with.

And what’s this about ‘calling a bluff’? For what? Justin could have simply identified his apostolic sources from the beginning and his point is made. However, there is yet a more fundamental problem with the notion that Justin was bluffing to Trypho – namely, there was no Trypho. The general scholarly consensus is that Trypho is a literary fictional character invented by Justin for rhetorical purposes. As such, Trypho did not exist as a bona fide recipient of this text to actually respond to Justin’s claims.

And finally, while I think Justin’s “memoirs” certainly bear some literary relationship to the four Gospels, it is worth noting that no verbatim quotes or citations from the canonical gospels as we have them appear anywhere in Justin’s extant works. This is particularly telling since Justin was careful in his citations from the Old Testament (and actually referenced his OT source material BY NAME).

Ok, I will endeavor to respond to the other items in your comment above. Until then, take care…

LikeLike