Daring to Ask…

How did the Gospel writers come to know the stories they shared? Were the writers themselves witnesses to the events they describe, faithfully recording the testimony of their experiences with Jesus? Perhaps they were told about them through “oral traditions”? To begin with, none of the New Testament gospels claim to be written by an actual eyewitness, nor are any eyewitnesses explicitly sourced or identified in these texts (see article: Yes, the Four Gospels Were Originally Anonymous). What’s even more telling is that the Gospels are narrated completely in the third-person omniscient voice, a narrative method that is a hallmark of Jewish and Greco-Roman fictional literature. This form of composition is not a feature of any authentic eyewitness biography or historical text from antiquity. In every example of literary narrative from antiquity where we find the constant and exclusive presence of the omniscient third-person narrator, the text was a fictional or allegorical tale –think Homer’s Iliad & Odyssey or the works of Euripides or even Jewish apocryphal books. This realization has to be factored into how we understand and examine the Gospels genre in proper context, as it sheds important light on how these writings would likely have been received by their original contemporary reading audiences.

Indeed, the Christian “gospel” as a genre may have its conceptual origins with Roman emperor Caesar Augustus (reign: 27 BC to 14 AD). During his reign Caesar Augustus was proclaimed “Son of God” and “Savior of the World” who “wiped away sins” –as is etched on an inscription at Pergamon.[1] The calendar inscription of Priene (dated to 9 BC)  pronounces of Augustus “the birthday of the god who has been for the whole world, the beginning of the gospel.” This reads strikingly similar to the opening of Mark 1:1, our earliest Christian gospel, which states: “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus the Christ, the Son of God.” We see also in Luke’s gospel the angelic proclamation of Jesus’ birth, “glory to God in the highest, peace on Earth and goodwill toward the men with whom He is pleased” (Luke 2:14). In the same vein, Augustus was believed to have been miraculously conceived by his mother, Atia, via the Roman deity Apollo (Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, 94.4).

pronounces of Augustus “the birthday of the god who has been for the whole world, the beginning of the gospel.” This reads strikingly similar to the opening of Mark 1:1, our earliest Christian gospel, which states: “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus the Christ, the Son of God.” We see also in Luke’s gospel the angelic proclamation of Jesus’ birth, “glory to God in the highest, peace on Earth and goodwill toward the men with whom He is pleased” (Luke 2:14). In the same vein, Augustus was believed to have been miraculously conceived by his mother, Atia, via the Roman deity Apollo (Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, 94.4).

In view of the aforementioned motifs first associated with Emperor Augustus accompanied by grandiose rhetoric that unmistakably overlaps with New Testament Christological concepts, is it possible that the Christian gospels were the product of pagan influenced syncretism and cultural diffusion? The evidence certainly supports that notion. Given that Christianity developed along the cultural margins of the Roman Empire, wouldn’t it be fitting that the gospels are a blend of pagan and Jewish concepts, cultural memes, and rhetoric?[2]

The All-Seeing Eye of the Gospel Writers

What exactly is the “third-person omniscient voice”? It is a literary device in which the narrator is all-knowing and fully privy to all pertinent details concerning the characters and events of the story, sharing with the reader numerous insights, scenes, and specific interactions lacking any credible eyewitness. The storyteller conveys with intimate knowledge episodes that would otherwise be unknown from an eyewitness standpoint. The author can be inside the minds of people, know their private thoughts and feelings, take part in private scenes and private conversations without being present, and can even be in two places simultaneously. As explained by renowned literary critic M.H. Abrams, the “omniscient point of view” affords a tell-tale signal that a narrative is a fictive work in that:

- the narrator knows all that needs to be known about the agents and events;

- the narrator is free to shift through time and place from character to character, reporting as he chooses what is said and done;

- the narrator knows the thoughts and feelings and motives of the characters as well as their overt words and actions; and

- the narrator is free to not only ‘report’ but also to comment on his characters[3]

The New Testament gospels embody each of the aforementioned literary features for fictive narrative. In appraising the plausibility of eyewitness content in the gospels, it is all well and good if the stories involved incidents of Jesus with his disciples. But as we shall see, numerous key scenes relayed in the gospels involve occasions where there were no ostensible witnesses; thus the notion that the gospel accounts are rooted in “eyewitness testimony” simply does not hold. To illustrate, consider the following examples:

The Matthean Nativity

The penchant for the New Testament gospels to convey narrative details beyond the scope of plausible eyewitness knowledge goes all the way back to the Nativity story. Matthew writes that upon Jesus’ birth, King Herod secretly summoned foreigners called Magi traveling from the East to “find out from them the exact time the [Bethlehem] star appeared” (Matt. 2:7).[4][5] Matthew had knowledge of other exclusive details including Herod’s verbatim instructions to the Magi to search for the residence of Jesus and to report back to Herod the child’s exact location. Somehow Matthew also knew that upon the Magi’s departure from Bethlehem, they were then warned in a dream to distrust Herod and to avoid the king by taking an alternate route back to their home country. Joseph himself was ostensibly unaware of all these background details and became alerted to Herod’s nefarious interest in Jesus only after Joseph, too, was subsequently warned in a dream to leave Bethlehem with his family and flee to Egypt. (Matt. 2:8-12)

How exactly did Matthew know these secret dealings between King Herod and the Magi? We read details only an omniscient narrator could know — the mental state and agitation of King Herod, the secret conversations between Herod and the Magi, and Matthew even knows about the Magi’s clairvoyant dream and their detoured travel route back to their home country east of the Tigris River.

Pontius Pilate, the Chief Priests, and Pharisees

Example #1: Matthew reports details of a private conversation between Pilate and the Pharisees the day after the death of Jesus, while all the disciples were hidden out of sight from authorities. In Matthew 27:62-65 we find the following:

“The next day, the one after Preparation Day, the chief priests and the Pharisees went to Pilate. “Sir,” they said, “we remember that while he was still alive that deceiver said, ‘After three days I will rise again.’ So give the order for the tomb to be made secure until the third day. Otherwise, his disciples may come and steal the body and tell the people that he has been raised from the dead. This last deception will be worse than the first.” “Take a guard,” Pilate answered. “Go, make the tomb as secure as you know how.” So they went and made the tomb secure by putting a seal on the stone and posting the guard.”

On what basis is Matthew providing us with these details? He certainly was no witness to this discussion, nor were any of the other disciples. Nowhere does Matthew provide his basis of knowledge for this information which derived directly from Jesus’ enemies. Matthew just somehow knows.

Example #2: Mark’s gospel purports to know what Jesus’ enemies (the scribes and chief priests) said among themselves in closed company when they were “scheming secretly to arrest Jesus and to have him killed.” (Mark 14:1-2).

Example #3: The gospel writers relate yet another private conversation, this time between the High Priest Caiaphas and his chief priest regarding their plot to kill Jesus. Matthew reports that they secretly schemed to have Jesus arrested, saying amongst themselves “but not during the Passover festival. . . or there may be a riot among the people.” Matthew is inexplicably privy to this private strategic discussion between two of Judea’s highest ranking religious officials (Matt. 26:3-5). In the same way, the gospels purport to know the specific details of another clandestine conversation between Judas Iscariot and the chief priests down to the dollar amount that Judas agreed upon to enact his betrayal.

Example #3: The gospel writers relate yet another private conversation, this time between the High Priest Caiaphas and his chief priest regarding their plot to kill Jesus. Matthew reports that they secretly schemed to have Jesus arrested, saying amongst themselves “but not during the Passover festival. . . or there may be a riot among the people.” Matthew is inexplicably privy to this private strategic discussion between two of Judea’s highest ranking religious officials (Matt. 26:3-5). In the same way, the gospels purport to know the specific details of another clandestine conversation between Judas Iscariot and the chief priests down to the dollar amount that Judas agreed upon to enact his betrayal.

A Brief Digression on Judas

What makes the Judas betrayal story odd as a historical event is the notion that Judas was needed to identify Jesus in the first place. Taking into account Jesus’ numerous public run-ins and debates with the religious authorities, Jesus forcibly clearing the Temple in the presence of armed Temple guards and authorities[6], that he entered Jerusalem in a high profile public procession during the largest Jewish holiday festival, combined with the notion that Jesus was essentially unable to move about Palestine unobserved and was readily recognizable to the general public –if we grant all of this for argument’s sake, then Judas would hardly be needed to specifically point out Jesus to the Jerusalem religious authorities. As if the chief priests would have to ask, “hey, which one of you guys is Michael Jackson?” To be sure, they were there to arrest Jesus because of his dangerous popularity.

Furthermore, there was no Jewish custom or procedural legality requiring a liaison to identify an individual being arrested. In fact, Jewish historical texts and the New Testament are replete with examples of Jewish authorities seizing people without the involvement of any go-betweens (see, e.g., Acts 4:1-4). Anyone associated with the priests, the Pharisees, or someone from among the armed Roman cohort could easily have shadowed a prominent group like Jesus and his entourage. Resorting to paying someone 30 pieces of silver to identify an essentially famous and well-known nemesis hiding in plain view is a notion that strains credulity. As history, the Judas betrayal scenario seems quite implausible. But as a story, these sort of narrative oddities are commonplace as a plot device.

What’s In a Name?

To that point, “Judas Iscariot” seems to be a moniker that carries some symbolic relevance to the gospel narrative. The name Judas as found in New Testament manuscripts is Ioudas or alternatively Ioudaios, meaning literally “People of Judah.” This symbolic use of names is likewise captured in the appellation Iscariot, though the exact meaning is uncertain. Iscariot (the term “Iskarioth”) is thought by some scholars to be a transliteration of ish-Qeriyot (meaning “of Keriot”), a town in Judea that was reputed for having produced men of poor character. The epithet could have also been intended as a double entendre. Linguist scholars point out that the etymology for Iscariot appears to derive from the Aramaic אִשְׁקַרְיָא, which means “the false one” or “one who betrays.” When we put it all together, the full moniker of Judas Iscariot would mean “The False Jews” or “The Jewish People Who Lie/Betray.”[7] From a thematic perspective, the disciple Judas symbolically personifies the contingent of Jewish people who, according to New Testament accounts, rejected and turned their backs on Jesus –ultimately being responsible for killing their own Messiah (cf 1 Thess. 2:14-16; Matthew 27:25; John 7:1)[8].

When character names in a narrative just happen to dovetail so perfectly with plot motifs and with the character’s purpose in the story, this is a tell-tale signal of literary gloss and creative license. The New Testament gospels (and much of ancient Greco-Roman literature) often give punning names to characters and incorporate double entendre wordplay in this fashion to signal metaphoric narrative utility. If a text contains only one instance of this, then perhaps it can be dismissed as mere coincidence and nothing more. But when there are multiple examples, then that is strong evidence of an author’s literary intent (other examples include Jairus, Barabbas, Joseph of Arimathea discussed further in the footnote).[9]

The Centurion at the Cross

In another example of third-person omniscient narration, Mark reports that upon the death of Jesus on the cross, the Gentile centurion who stood facing Jesus confessed “Truly this was the son of God.” But as history, how could Mark have known those words? None of the disciples were present with the centurion. Each of the Synoptic gospels emphasize that Jesus’ disciples fled and deserted him upon his arrest to remain hidden out of sight, and even the women looked “from afar off.” (Mk. 15:40)

John the Baptist and Herod

Consider also the scene of John the Baptist and Herod the tetrarch. The authors of Mark and Matthew reported the interaction between John the Baptist and Herod while John was imprisoned in the private confines of Herod’s quarters. Similarly, and equally perplexing, the Gospel of Mark even purports to know of a conversation between Herod’s wife and his daughter Salome regarding the fate of John the Baptist. How did the writer come to know such exclusive details? Once again, none of the disciples were present for these events. And unlike other ancient historical writings from that time, the gospel writers fail to provide any plausible source or circumstance for such knowledge.

It’s All Greek to Matthew

This final example from Matthew’s gospel is especially intriguing and requires in depth discussion. Again, bear in mind that according to the Synoptic gospels, neither the disciples nor the women were present at the crucifixion. Yet, the Gospel of Matthew recites the specific words spoken by the chief priests and scribes to mock Jesus at the foot of the cross. Matt. 27:43 reports in pertinent part that the religious leaders taunted Jesus saying, “he trusts in God; let God rescue him now, if He delights in him.”

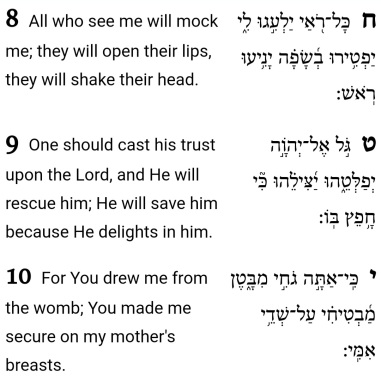

These words purportedly spoken by the religious leaders to mock Jesus at the cross just so happen to track nearly word-for-word with Psalm 22:8 as taken from the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (the Greek version of the Old Testament is known as the Septuagint). Psalm 22:8 from the Septuagint reads: “He trusts in the LORD, let the LORD rescue him. Let him deliver him, if he delights in him.”

Beyond the fact that the disciples and women were not present with the chief priests at Golgotha to either witness or hear them serendipitously parrot Psalm 22, a second problem is that Psalm 22 as found in the Greek version of the Old Testament is in fact a mistranslation of the original Hebrew –and this corruption has altered the original meaning. This, in turn, has led to problematic consequences for Matthew’s story. The author of Matthew (a Greek speaking Jew) relies on this mistranslated rendering of the Psalm 22 passage, then transfers this improper context over to his gospel narrative –as if the events he describes were in accordance with scripture. A full appreciation of this awkwardness first requires a brief discussion on the Greek Old Testament.

The Bible from Hebrew to Greek

The Old Testament was first composed in Hebrew. After the Babylonian captivity, Jews in Palestine eventually began to speak a related Semitic dialect called Aramaic (portions of Daniel and Ezra are written in Aramaic). Prior to the New Testament there were diaspora Jews who branched out beyond Palestine into Hellenistic territories. These Jews were aptly dubbed ‘Hellenistic Jews’ because they began to assimilate and integrate Gentile/Greek customs, philosophy, and the Greek language into the Jewish culture. As time passed, Hellenistic Jews spoke Greek as their principle language, and the majority of them could no longer communicate in Hebrew/Aramaic or even read the Old Testament scriptures in the original language as could their Hebraic Jewish counterparts who remained in Judea-Palestine (i.e., the priests and Pharisees in Judea still spoke Aramaic and could read Hebrew). In order for educated Jews outside of Judea to have access to Old Testament scriptures, it became necessary to translate the Hebrew Bible into the Greek language.

This Greek Old Testament (called the Septuagint) was unfortunately encumbered by mistakes and translation errors. These errors involved numerous word mistranslations and misconstrued renderings of passages that altered the original meaning and context of the Hebrew scripture. The intended ideas, words and context often got lost in translation, which led to peculiar results when the New Testament gospel writers relied upon or quoted from the Septuagint.

Let’s now return again to Matthew chapter 27. Matt. 27:43 says that the religious leaders taunted Jesus at the cross saying, “he trusts in God; let God rescue him now, if He delights in him.” This is in agreement with the Greek version of Psalm 22:7-8, which reads:

“All who see me mock me; they make mouths at me; they shake their heads at me saying, ‘he trusts in the LORD, let the LORD rescue him. Let him deliver him, since he delights in him.’”.

Looking at the Greek version, Psalm 22:7 appears to prompt a sarcastic taunt from the Psalmist’s enemies that follows in verse 8. The problem is that this reading of Psalm 22 from the Septuagint deviates from the meaning and context of the same passage as found in the Hebrew Bible. So, how does this same passage read in the Hebrew Bible? Turns out that this scripture in Hebrew carries the opposite context and sentiment. The Hebrew Tanakh reads:

As we see in the original Hebrew, the context of this passage is actually an expression of the Psalmist’s own affirmative declaration of divine assurance and his trust in God in the face of his enemies’ mockery. Despite having detractors, the Psalmist resolves that one should trust in God, and He will indeed deliver you. That’s the clear premise of the passage. Psalm 22:8 is not a taunt of mockery as found in the Greek translation; rather, it’s the antidote to attacks and mockery as seen in the original Hebrew language.

However, the translators of the Greek Old Testament confused the context and thus altered the passage so that Psalm 22:7/8 reads as a taunt of mockery uttered by the Psalmist’s opponents. Consequently, when the author of Matthew’s gospel makes prophetic application of Psalm 22:8 using the Septuagint, he places the taunt of sarcasm (i.e., the errant translation) into the mouths of Jesus’ enemies at the cross as if their jeers were somehow word-for-word fulfillment of genuine Old Testament prophecy (when, in fact, Matthew actually records a corruption of Psalm 22. Oops!).

From this we discover that Matthew has tipped his hand as to how he constructed his gospel narrative –at least with regard to prophecy. We can observe that Matthew’s telling of the story was not a genuine fulfillment of prophecy (because the Hebrew source text is contextually different from what Matthew inserted into his narrative). What we find instead is that the narrative events depicted in Matt. 27 were derived from what Matthew thought the Old Testament said, and he imported this into the story. Put simply, Matthew created his narrative to comport with Old Testament scriptures, not the other way around. Similar gaffes are sprinkled throughout the gospels.

The Gospels Compared to Secular Ancient Historians

Proponents of the view that the New Testament gospels are bona fide “eyewitness” accounts often say that we shouldn’t hold the Gospel writers to the standards of modern day historians and biographers; that we should instead evaluate the Gospels in accordance with the customary practices of Greco-Roman and Jewish historians during that time. But even under that rubric the Gospels do not pass muster as plausible historical eyewitness accounts. Consider this: every known historian, biographer, and social commentator during the early Roman Empire who dealt with subjects dating to within a generation or two of his own lifetime—Josephus, Cornelius Nepos, Tacitus, Justus of Tiberias, Pliny, Seneca the Younger, Plutarch, Suetonius, and Lucian—all use the first person singular to discuss their own personal association to their sources and the biographical subject. Not a single one of them defaults to the perpetual use of the omniscient third-person narrative voice.

Famed apologist J. Warner Wallace still maintains that we cannot “scrutinize or question the New Testament gospels any more than we can doubt the historical claims of other historians and biographers that we acknowledge in antiquity. If we can’t accept these four complementary [gospel] accounts, we can’t trust much of anything we claim to know about ancient history from any source.” Thomas Paine’s statement in Age of Reason perfectly addresses Wallace’s contention. Paine writes:

“As to the ancient historians, from Herodotus to Tacitus, we credit them as far as they relate things probable and credible, and no further: for if we do, we must believe the two miracles which Tacitus relates were performed by Vespasian, that of curing a lame man, and a blind man, in just the same manner as the same things are told of Jesus Christ by his historians. We must also believe the miracles cited by Josephus, that of the sea of Pamphilia opening to let Alexander and his army pass, as is related of the Red Sea in Exodus. These miracles are quite as well authenticated as the Bible miracles, and yet we do not believe them; consequently the degree of evidence necessary to establish our belief of things naturally incredible, whether in the Bible or elsewhere, is far greater than that which obtains our belief to natural and probable things.”

In other words, if we’re being consistent and objective in our historiographic assessments across the board as J. Warner Wallace insists, treating the gospels just as we do other secular historical sources from antiquity, then we’d be forced to also accept as historically true the aforementioned miracles chronicled by those secular writers (even more so since those writers have a much better track record of naming their sources or otherwise providing the basis for their claims). But, if we are nonetheless reluctant to grant historical credence to miraculous and other incredible claims from Herodotus, Josephus, and Tacitus, then a consistent historiographic assessment of the gospels requires the same. Contrary to J. Warner Wallace’s contention, we’re not privileging other secular sources more than the gospels.

Another explanation is that God inspired the evangelists to write things that only an all knowing God would know. By all means, you may appeal to supernatural explanations to account for the narrative details in the Gospels. But the moment at which you appeal to such explanations, you have entered into the realm of theology and have abandoned the historical method –which is your prerogative. Still, it is worth noting that none of the gospel writers ever claimed to have written under divine inspiration or by way of revelation. The notion that the four gospels were divinely inspired is an ad hoc assertion imposed upon the gospels after the fact by the post-apostolic Church community.

Conclusion

Are the gospels faithfully reporting firsthand eyewitness history, or did the writers instead take narrative license to create a story? That’s for you to decide for yourself. But consider the poignant perspective of influential early Church father Origen. Origen explains that those who read the Gospels as actual historical narratives are perhaps being naively literal, and that the gospels were constructed as historicized allegory and were not to be taken literally as many have done (note: early Patristic Fathers such as Irenaeus and Papias have similarly challenged a strict literal rendering of gospel narratives in favor of spiritual/parabolic renderings). In his treatise titled Contra Celsus, Origen states that “the historical parts” of the Gospels “were written with an allegorical purpose, being most skillfully adapted not only for the multitude of simple-minded believers, but also for the few who are willing or even able to examine matters intelligently.” He goes on to state that those who approach the text literally “have a veil of ignorance upon them. What other inference can be drawn than that [the gospels] were composed to be understood allegorically as their chief designation?” Origen boils down his point as follows: “the spiritual truth was often preserved, as one might say, in material falsehood.”

All that to say, Origen has a point… the totality of evidence is compelling in showing that the New Testament gospels are not reporting firsthand eyewitness accounts of history. And those who nonetheless maintain that the gospels are firsthand eyewitness narratives bear a special burden of proof to justify this insistence. As it happens, early Christianity and New Testament studies is an arena where people tend to engage in theology & tradition and call it history or biography. To paraphrase the esteemed John Dominic Crossan, over the years of scholarly research we have learned that the gospels are not history, though they contain some history. They are not biography, though they may contain some biographical elements. They are gospel narratives, and as we observe from the prototype example of Caesar Augustus, the value in the messages and motifs of these narratives often supercede historical and eyewitness reality.

[1] (Elegies 4.6.37-9)

[2] D. Aaron Hill

[3] ‘A Glossary of Literary Terms’ (M. H. Abrams, 8th Ed., 2005)

[4] I have decided to credit the traditional gospel authors here out of convenience, even though the general consensus among scholars is that the authorial attributions to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are post-hoc titles appended pursuant to Patristic ecclesiastical traditions, as opposed to them being self-attributed titles by the original authors of the gospels. I offer detailed discussion of this topic in my articled titled: ‘Yes, the Four Gospels Were Originally Anonymous’

[5] Magi were Zoroastrian priests from old Persia who practiced astrology and divination. The word magi is the root from which our words “magic” and “magician” are derived.

[6] The historical plausibility of the Temple cleansing incident is itself tenuous. The Jerusalem Temple grounds were massive occupying nearly forty acres, and a large portion of that, at least ten acres, was devoted to public space. The court and interior quarters were extensively populated, and there would have been hundreds of merchants and moneychangers there. The Temple was the economic epicenter of Judea. Most importantly, the Temple was heavily guarded by an armed force deployed to prevent just the sort of disturbance described of Jesus in the gospels. There had been prior attempted disturbances and rebel uprisings at the Temple, and they were swiftly put down by the armed cohort. If Jesus had really gone –alone– into the massive Temple with a whip to expel hundreds of merchants and moneychangers, the guards would have either killed Jesus on the spot, or at a minimum seized him to be hauled away for insurrection. Open and shut. Gospel story over. So the story of Jesus cleansing the Temple is historically tenuous on that point alone.

[7] “Judas Iscariot: Revealer of the Hidden Truth” (Israel Jacob Yuval, 2011).

[8] In the Gospel of John, the phrase “the Jews” is used in a derogatory sense at least 31 separate occasions.

[9] In the gospels, Jairus had a daughter who “fell asleep” (i.e., she died). Jesus miraculously awakened her (brought her back to life). We don’t know the young girl’s name. The only name given is that of her father Jairus, which conveniently, means ‘God will awaken.’

The name of the insurrectionist Barabbas means “son of the father” (a very unusual name). Some gospel manuscripts even have the name as Jesus Barabbas, which would translate to “Jesus -son of the father.” So we have two men alongside each other both styled as “son of the father.” One is guilty yet released as the scapegoat, while his innocent counterpart with the same moniker has to be sacrificed to bear the sins and blood lust of the people. This is a narrative replication of the Yom Kippur ritual set forth in Leviticus 16 where two identical goats were chosen each year, and one was released into the wild (the scapegoat), while the other goat’s blood was shed to serve as atonement for the sins of the people.

It’s nice to see blogs publish new content after a long hiatus – it makes me feel better about my own languishing blog.

I seem to recall that you have been in the Jesus mythicist camp (apologies if I got that wrong). I see signs of both mythicist and historicist thinking in this post. What is your current leaning?

LikeLike

Hi, Travis. Thanks for your question. Yes, you recall correctly. I did lean toward the view of Jesus as ahistorical, but not dogmatically so. At the present I would consider myself agnostic on the matter.

I am curious to know which portions of my blog post you see as mythicist thinking versus historicist thinking. I was not intending to put forth a specific perspective. So, it interests me to find out how my analysis came across to you as a reader.

LikeLike

The early parts which discuss pagan influences and genre had a bit of a mythicist feel to it – I feel like mythicists often overstate the gentile influence. But then the textual comments and conclusion seemed to be allowing for embellishment on a historical core and incorporating the Jewish context more like a historical perspective would.

LikeLike

Ok, I see. The extent to which the Jesus gospel and early Christianity have been shaped by Gentile influences is a matter of case by case assessment. The example cited in my blog post is quite probative of such syncretic dynamics in my view. Having said that, I don’t think it necessarily denotes a mythicist conclusion by any means. This is made apparent in the cited pagan example of Caesar Augustus. Augustus was not the savior of the world, nor was he the son of god who wiped away sins. His mother did not conceive him through divine impregnation. Yet, Caesar Augustus was a bona fide historical figure. What we have here are grandiose symbolic embellishments. The same could be said of Jesus without appealing to a mythicist conclusion.

LikeLike

Of course, this is all explained away with the fiction that the gospel writers were inspired and guided in their writings by “the Holy spirit.”

LikeLike

Yes, and I addressed that apologetic in my article as follows:

“Another explanation is that God inspired the evangelists to write things that only an all knowing God would know. By all means, you may appeal to supernatural explanations to account for the narrative details in the Gospels. But the moment at which you appeal to such explanations, you have entered into the realm of theology and have abandoned the historical method –which is your prerogative. Still, it is worth noting that none of the gospel writers ever claimed to have written under divine inspiration or by way of revelation. The notion that the four gospels were divinely inspired is an ad hoc assertion imposed upon the gospels after the fact by the post-apostolic Church community.”

LikeLike